Throughout my research across the broader family tree, I have found many occasions when the first child of a family (sometimes more than just the first child) is born before the parents marry. I have also found cases where the parents do not marry, and/or go on to marry other people. Therefore, I was interested to follow James Roy and Anne Peddie over the years subsequent to William I's birth to see what happened with them.

So, did they marry? The short answer is, no. Not to each other.

Without any concrete evidence, I can only make guesses as to what their circumstances were. One of the possible scenarios is that James, a 21 year old farm labourer, did not have the economic capability to marry at that time - which would have required him to set up his own household. Maybe his own family didn't approve of Anne, or they didn't have the ability to support another family in their own household? Perhaps there was never an intention of a permanent relationship, and William was the result of a one-off encounter? Maybe James and Anne just didn't like each other enough to marry? Perhaps James was already committed to someone else? We will never know the details of their situation.

James' family were farmers at Glack, which was a small hamlet a few miles from what became the village of Bankfoot. The map below, from a slightly later era (1850s -1860s) shows the outlines of the buildings at Glack and nearby Balquharn and Gibbeston.1 Anne was nine years older than James, and had been working as a servant to John Fisher at Glack for 'a few years'.2

|

| Image reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. |

By the time she was called to the Kirk Session, Anne had left Glack and was living in Little Dunkeld. The most likely explanation is that she went back to her own family as she awaited the birth of her child. If that is the case, she would have been living at Ballinloan - another small hamlet, which is about 4.5 miles (7.25 km) in a straight line from Glack (see image below), but is separated by a range of hills.

|

| Image reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. |

James Roy of Bankfoot had a son by his wife, Jane Dow, born this day and baptized - named - James.4

Although I cannot find a marriage register entry for James and Jane, we can surmise from the words 'his wife' that they had already married - nothing got past those parish clerks, they wouldn't have written wife unless she officially was.

And in Little Dunkeld, when William Roy I was almost six years old, Anne married John Cowan:

January 6th 1817, John Cowan, Parish of Auchtergaven and Anne Peddie in this, one sabbath and no objections. 5

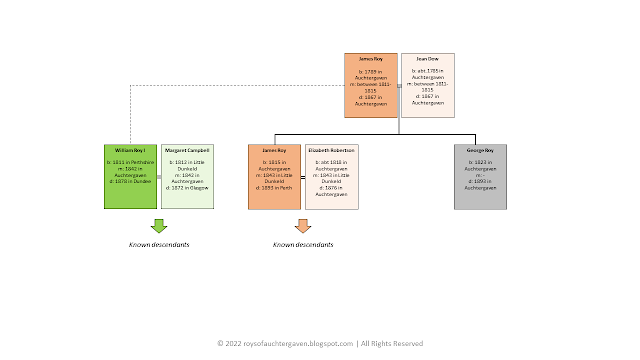

Children of John Cowan(s) and Ann(e) Peddie (click to make larger)

Children of James Roy and Jean/Jane Dow (click to make larger)

There's still a lot of work to be done in following each of these branches, but my initial thoughts are that:

- William Cowans and Ann Fenwick ended up in Glasgow, very near to where William Roy II lived.6

- Is it possible that Peter Cowans married Grace Stewart and emigrated to Ontario in Canada where he was a farmer with multiple children and died there in 1881.7

- George Roy never married and died a pauper at Waterloo in Auchtergaven in 1893.8

- In the same year, George's brother James died in Perth. He had married Elisabeth Robertson and they had seven children, but four of them died between the ages of 9 and 22. The three others have not yet been traced.9

2. Auchtergaven kirk session, Minutes (1808-1855) and Proclamations (1855-1861), Session 15th, 24 March 1811, National Records of Scotland, CH2/22/2, Images 00007 and 00009.